Police brutality must be stopped

My name is Adil Shamsuddin, and I will be taking you on a journey, allowing you to understand the abysmal situation called police brutality. Police Brutality Is something I feel deeply about, this is something that need to be stopped because, we are losing people who have a right to live. This incident usually appears throughout the whole world, but, it's commonly known throughout the areas of washington and new york. Police Brutality “is the use of any force exceeding that reasonably necessary to accomplish a lawful police purpose. Although no reliable measure of its incidence exists—let alone one charting change chronologically—its history is undeniably long”. A lot of people ask themselves this question, why is Police Brutality a thing. Police Brutality had started in the time period of 1874, in new york, when a local police force, started to beating protesters during the Tompkins Square riot.

this is a picture of Eric Garner, this is important because this allows us, to under the wrong of this situation. “NYPD officers approached Garner on suspicion of selling cigarettes. “After Garner told the police that he was tired of being harassed and that he was not selling cigarettes, the officers went to arrest Garner. When officer Daniel Pantaleo tried to take Garner's wrist behind his back, Garner pulled his arms away”. The most outrageous thing is, the people who was around this situation, had either, record their camera out, or just stood there.

this is a picture of Eric Garner, this is important because this allows us, to under the wrong of this situation. “NYPD officers approached Garner on suspicion of selling cigarettes. “After Garner told the police that he was tired of being harassed and that he was not selling cigarettes, the officers went to arrest Garner. When officer Daniel Pantaleo tried to take Garner's wrist behind his back, Garner pulled his arms away”. The most outrageous thing is, the people who was around this situation, had either, record their camera out, or just stood there.

This topic is very outgoing towards the way i think because, I want to see a change in the world. I want to see people go outside and enjoy there day without thinking negative towards, if either they would be attacked by an officer who's having a bad day, or just killed by gunfire by a police force because they thought he or she had a gun. “Police killed at least 303 black people in the U.S. in 2016”. Through the board of justice, the supreme court has no approval of this. “The Supreme Court doesn’t decide a lot of police shooting cases, but when it does, it tends to side with the officers. And increasingly it does so in unsigned rulings for which it doesn’t bother to hold oral arguments”.

this rate is explaining to us how many african americans were killed, or face Police Brutality. This chart in between january 2013- september 2016. The numbers started to rise very high throughout the time period of 7/1/14, it drops done nearly at 1/1/15. Also not only it dropped down, it rose even higher around the months of 7/1/15.

this rate is explaining to us how many african americans were killed, or face Police Brutality. This chart in between january 2013- september 2016. The numbers started to rise very high throughout the time period of 7/1/14, it drops done nearly at 1/1/15. Also not only it dropped down, it rose even higher around the months of 7/1/15.

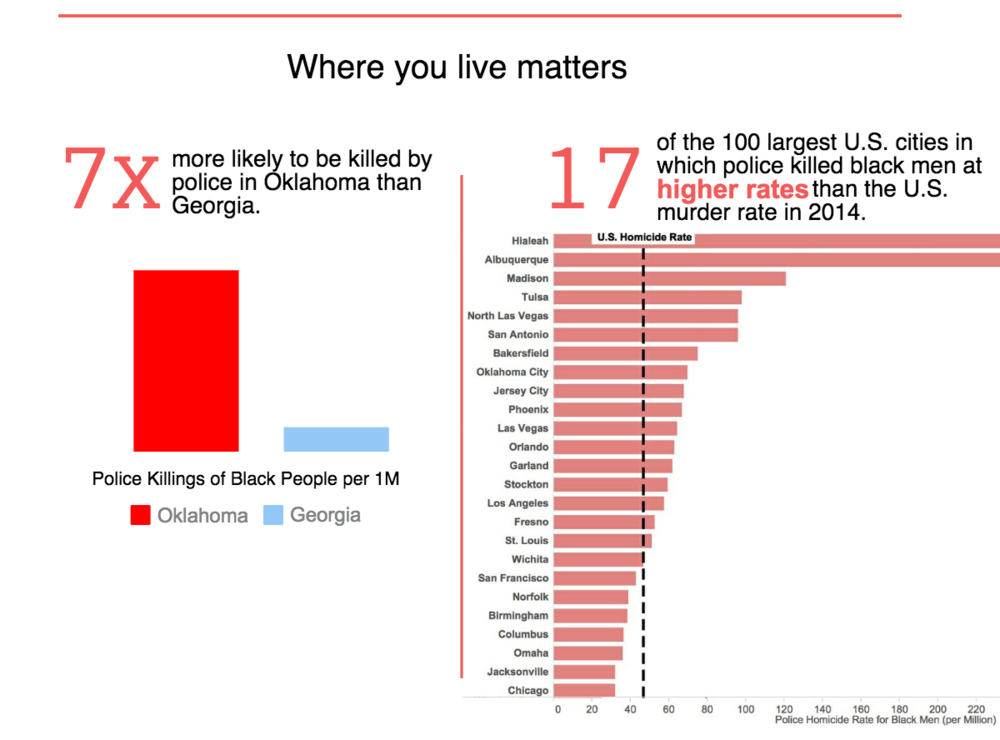

these are rates of how much Police Brutality a city face. Not only people faced it around New York and etc, the highest rate of homicide are hialeah. This bar rate is on a average on how many homicides were faced on African Americans, by themselves. This is also rated by per million, so this statistics are pretty full of amount.

these are rates of how much Police Brutality a city face. Not only people faced it around New York and etc, the highest rate of homicide are hialeah. This bar rate is on a average on how many homicides were faced on African Americans, by themselves. This is also rated by per million, so this statistics are pretty full of amount.

this was a march that was specifically for Eric Garner, this shows that not only people want to make a difference, they went out there way to do it. The passings of Garner, Brown, and others on account of Police are not by any means the only purpose starting mass dissents. The day after the Garner shows began, low-wage specialists strolled off their employments in more than 190 urban communities, requesting a living compensation and the privilege to sort out. They, as well, droned, "I can't relax." Workers from fast-food eateries, for example, McDonald's were joined by those from low-wage retail and accommodation stores and carrier benefit occupations.

this was a march that was specifically for Eric Garner, this shows that not only people want to make a difference, they went out there way to do it. The passings of Garner, Brown, and others on account of Police are not by any means the only purpose starting mass dissents. The day after the Garner shows began, low-wage specialists strolled off their employments in more than 190 urban communities, requesting a living compensation and the privilege to sort out. They, as well, droned, "I can't relax." Workers from fast-food eateries, for example, McDonald's were joined by those from low-wage retail and accommodation stores and carrier benefit occupations.

His PDA video of the last snapshots of Eric Garner's life set off a national discussion about policing and race, and gave the beginning Black Lives Matter development a motto: "I can't relax."

Presently Ramsey Orta will prison to serve a four-year sentence for offering heroin and unlawful ownership of a gun.

Orta, 25, saw the demise of Garner, who was limited in a strangle hold by New York City Police in Staten Island two years back. Police were keeping Garner for offering single cigarettes before a comfort store, and place him in a strangle hold to wrestle him to the ground.

Orta got the follow up on his wireless, including Garner's last words, "I can't relax." He then transferred the video to YouTube and enlivened others to get their mobile phones and record police activities the nation over. The officer required in the dangerous strangle hold — a move restricted under the New York Police Patrol Guide — was not arraigned for Garner's demise.

Here is my annotated bibliography